Just one city block down from Checkpoint Charlie on Niederkirchnerstraβe sits the Topography of Terror, a museum intentionally positioned at the site of the former headquarters for various notorious Nazi organizations such as the Gestapo and the Einsatzgruppen (a contingent of the Schutzstaffel, or SS; these were the specialized killing squads that ran riot behind the advancing German lines in the conquered territories of the East, rounding up and killing in mass Jews, Romani and Sinti peoples, as well as other perceived political or biological threats). Running along the front of the main museum building still stands the longest extant segment of the outer Berlin wall. The museum is one of my standard stops for students when we take our walking tour of downtown Berlin.

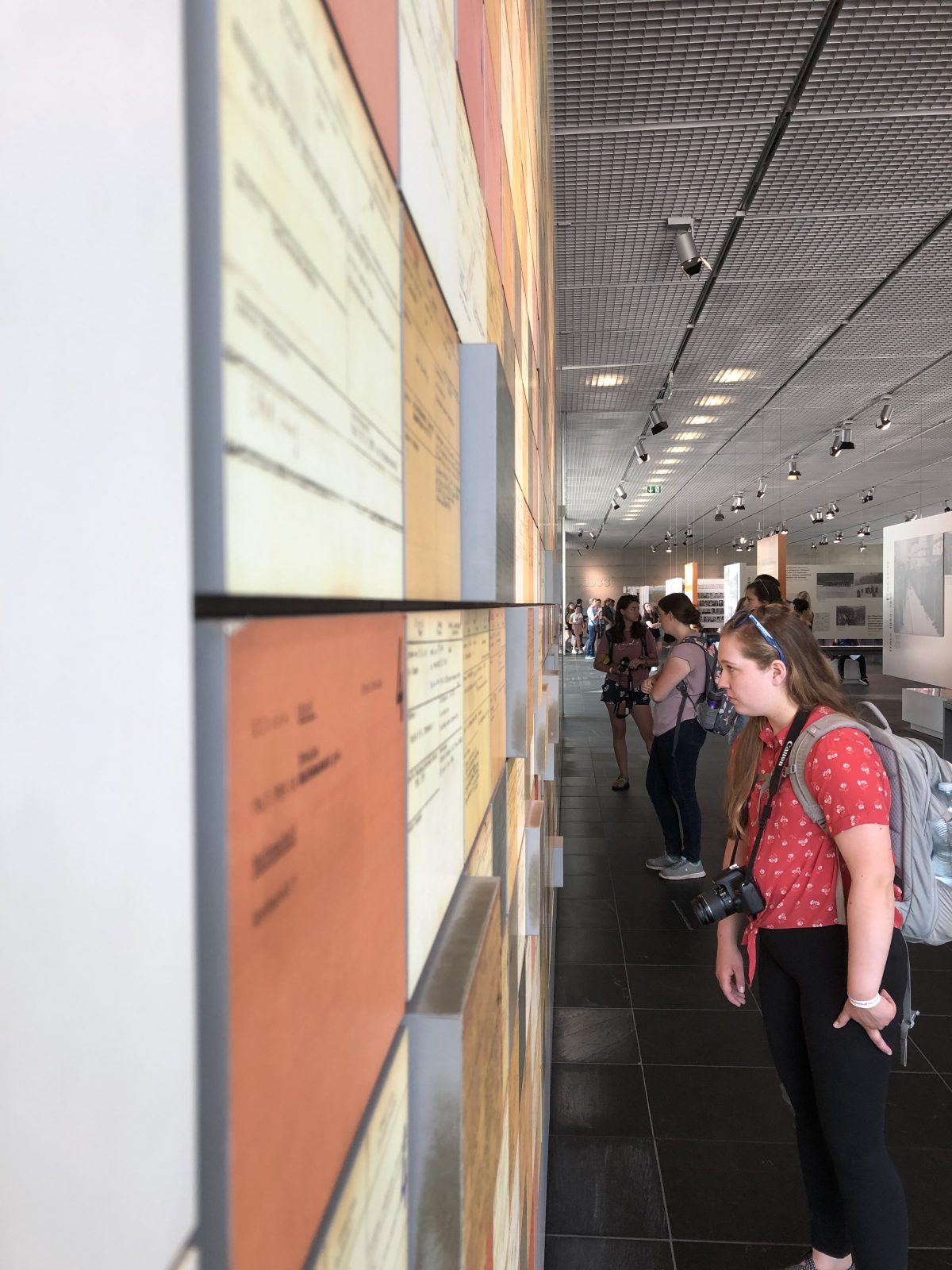

Inside the main building is an extensive document center and educational facility as well as many permanent and temporary exhibitions describing some of the most notorious crimes of the Third Reich. In the back left corner, covering a large section of an interior wall, sits an unusual and interesting exhibit that, despite its size, can easily be missed. It consists of nothing more than a grid of cards, each one containing a name, occupation, contact information, and a set of accusations. (See the picture to the right.) It is a large display, with 500 cards or more affixed to the wall. The exhibit label and description indicates that each card identifies a person who had worked in one of these notorious Nazi organizations and was, after the war, indicted as a perpetrator of criminal activity. A closer look shows that a smattering of these cards are raised off the wall – some by just a little, others by a bit more. Further reading tells us that the cards with the slightest raise indicates that particular individual was arrested; a bit more pronounced protrusion represents those who were arrested and went to trial; another degree of projection for those tried and found guilty; and those with the greatest relief were actually imprisoned, at least for some period of time for their crimes. Those resting flat against the wall were not even arrested.

What is striking is the scarcity of the raised cards compared to those that were flush against the wall. Only a small fraction of them are pushing outward, and only a scant few positioned with the highest relief. Looking at the display, one wonders if even 1% of these evil actors actually served time for their crimes. It is a powerful visual representation of injustice; a sorrowful story of a system that overwhelmingly failed the people it was supposed to serve. Even more sobering is the realization that this may be an accurate representation of injustice not just for the 12 years of Nazi terror experienced in Europe, but for the broader sweep of all human story. After all, history informs us that the vast, vast majority of victims throughout history have never seen justice. They were simply left abused and broken, discarded by tormenters who were never to be held account for their actions. This wall cleverly portrays the extent of injustice in post-war Germany, but it can also remind us of the legacy of injustice that has left an open wound, continuously being furrowed by the running of tears and blood, that runs bone-deep throughout the length and breadth of the human saga.

As I stood there taking in the exhibit, with my heart and mind awash with emotions and thoughts, my conscience became unwelcomely stirred. Might this wall also be a representation of my moral standing in relation to people I have wronged? If we flip-the-script a bit and consider each of those cards to represent not a perpetrator but a victim, a victim of my selfishness and insensitivity, my dishonesty, rationalizations, and sleight-of-hand, might this exhibit in some way reflect the injustice for which I am responsible? How many people wronged by me have received proper compensation? Have not I also simply walked away after hurting others, never having to answer for my actions? Further, I realized that the same in-principle defenses presumably used by these infamous walled names to exonerate themselves or mitigate responsibility would probably sound familiar to me. After all, was I not serving a greater good? Didn’t at least some of those people deserve what they got? Better them than me, right? One does not have to establish moral equivalency in the nature of the crimes to realize that the picture of sporadic and infrequent justice on display in that museum can be aptly applied to one’s own legacy in terms of the relationship between crime and punishment.

As I continued to consider the exhibit, I found myself now not only feeling for the victims, but also identifying, just a little bit, with the perpetrators. I identified with them in their hope to avoid capture or in some way to escape being called to account, and also in the rehearsal of defenses to be on-hand if needed. Though I scrambled to recover the initial lens I wanted to use to understand this moral landscape, that simpler and self-protective lens, I finally and begrudgingly had to admit that the other side of the coin, the perspective of the perpetrator, now necessarily looked just a little bit different – and it also looked just a little bit familiar.

As you exit the Topography of Terror Museum and look at the aged remnant of the Berlin Wall stretching out across in front of it, you see just below the wall the exposed results of a digging project. Recently, the long buried underground interrogation rooms of the Gestapo, places where countless people were mistreated and even killed, have been excavated. The terrible secrets contained in those rooms, once presumed to be hidden from an inspecting light forever, have now been unearthed and laid bare for all to see. The instruments of torture found, the scenes of the crimes uncovered. My conscience is once again unwelcomely stirred…