(Presented to students in the Honors Program at Asbury University, August, 2021.)

As you know, the honors experience here at Asbury is a themed enrichment program – our enduring theme is “Studies in Virtue and Human Value.”

One of our program’s guiding questions is, “What gives humans value and dignity?” We all feel valued or at least we feel like we should be valued, and most people are quick to affirm their belief in the dignity of all people. But just beneath this feeling and belief lies the question of “why.” Why do we have this feeling and belief that humans have inherent worth and dignity?

Perhaps, before we go much farther, we should first get to the “what” of intrinsic human value. What do we mean by that term? According to the Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity, “Human dignity is the recognition that human beings possess a special value intrinsic to their humanity and as such are worthy of respect simply because they are human beings.”1 Of course, there are other definitions, and the distinctions between them can be very important, but this is a good one to get us into the topic.

This evening, I want us to consider the prerequisite question of why; why we believe in human dignity. One way to pose the “why” question is like this: is the idea of human dignity something we invented or something we discovered?

Was it built by the hive-action of a collection of human minds like so many of our cultural customs and conventional practices? Is this something we have collectively thought up, perhaps to help us live peaceably with one another? After all, we have fashioned all sorts of important and powerful ideas to facilitate, standardize, and attempt to harmonize our social interactions. For instance, we have developed a vast assembly of customs for greeting one another and demonstrating mutual respect. These interpersonal actions demonstrate to one another our recognition of a person’s autonomy and value. We have also created ideas designed to manage the civic relationships between peoples. For example, we have created nation states (as well as the peace treaties between them), various types of government, laws, and societal norms and expectations. Though these constructed entities often fail and are discarded, the original stated intention, at least since the emergence of democracies, has been to protect people and promote human flourishing.

Turning to our psychological selves, an honest inside look will reveal that much of our claimed personal and professional identities are manufactured, not to mention the labels that we often attach to ourselves and which we encourage others to validate (e.g., athlete, poet, friend, or artist). Isn’t the social self largely an invention, its fluctuation across time and situation serving as an ever-present reminder of this? So much of who we claim to others to be is of our own making. Might this also be true for our claim of intrinsic value?

Or take our sense of morality, of right and wrong; is it also a product of human engineering? This is an interesting question. According to a recent book by Hunter and Nedelisky, “Science and the Good” (2018), most current scientists who study morality have given up on finding a bridge between describing the “is” of normative moral behavior and the “ought” of what it should be, deciding that there may not be any real oughts out there to be discovered. Well, perhaps we, like the authors of this book, should be suspicious of some claims of invention. However, one thing seems clear, many of the societal structures that give shape to our communities, and many of the concepts that give our individual lives meaning and purpose, the features of life we use every day to convey our value to others, are mere social constructions. They are inventions, and even though they sometimes wield immense power, they are not discovered truths.

Or was human dignity discovered – like a previously uncharted pacific island or a principle of reality uncovered through reflected experience like the Pythagorean theorem or gravity, or perhaps some aspect of biological life like the Y chromosome spotted under a microscope. These features of reality just exist. They were either woven into the original fabric of reality or they showed up sometime later; but whichever the case, they exist without a whit of care for human wishes or concerns. And we eventually just happened upon them; we discovered them. Unlike inventions, which we can manipulate and adjust as our need for them changes, things that are discovered are stubbornly independent of our hopes and desires. They simply are what they are. Take ‘em or…..well, you have to take ‘em. That’s the point. There is no choice in the matter. If humans genuinely possess intrinsic value, then there is nothing one can do to change that basic feature of reality.

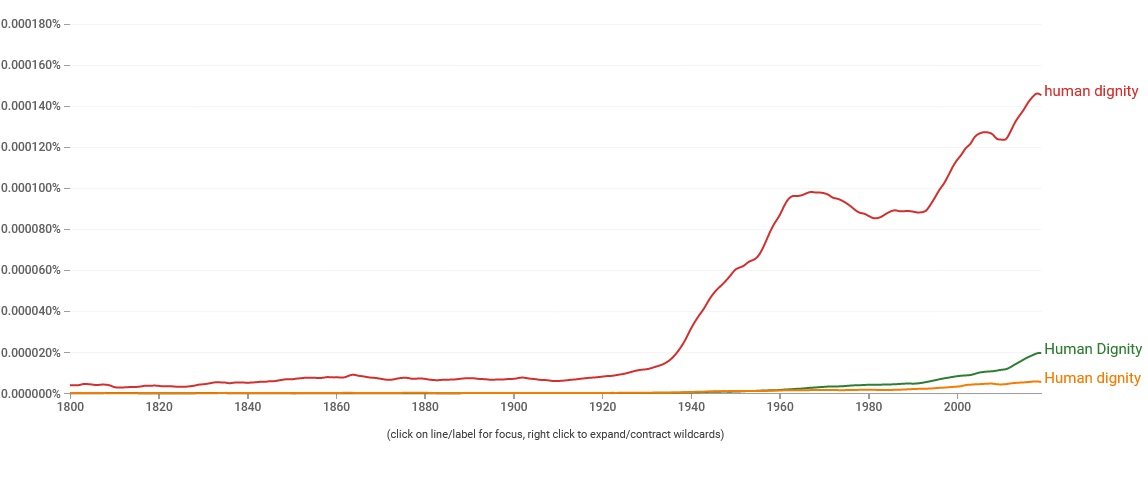

As we think about this question, note that a vast majority of currently existing laws that appeal to human dignity for their existence, as well as virtually all of the organizations that have the defense of human dignity in their mission statement have emerged recently, since the end of the Second World War. Also, note that the phrase,” human dignity,” is largely a post-World War II expression. In support of this claim, I offer an “Ngram” of the phrase (see figure to the right) which shows that it’s usage in English books was virtually non-existent until the 1940’s. The term “human dignity,” as it turns out, is rather contemporary.

Furthermore, it is rather easy to argue that the moral circle has been greatly expanding since the end of that terrible war, correlating well with the dramatic increase of the use of the term. I would guess that when our great-grandparents were growing up, they could not have imagined a world where so much effort and resource was given to such things as prenatal and neonatal health, widespread educational opportunities for those suffering from autism or cognitive challenges, and let’s not forget the increased access and opportunities for those with physical disabilities. An example of this might be the emergence of and global support for the Paralympic Games; an offshoot of the Olympic Games involving thousands of competitors from dozens of countries around the globe; these games were first held, by the way, in 1960.

“Dignity is a phenomenon of human perception…”

Steven Pinker, 2008 (The Stupidity of Dignity, The New Republic)

As you think about this question, let’s revisit the definition one more time, “Human dignity is the recognition that human beings possess a special value intrinsic to their humanity and as such are worthy of respect simply because they are human beings.” Notice it reads “recognition.” Is that true? Is it something that has always been there just waiting to be recognized, or is it an imagined idea with which we have eventually come to agree?

After struggling with this question for a bit, some might wonder, “Why does it matter whether human dignity was invented or discovered? Secular humanism says we invented it, orthodox Christianity claims it was discovered, but in the end, isn’t it just important that it now exists?” Let’s just be thankful and not worry about it.

Well, for several reasons, I suspect it does matter. Let me offer a couple of them for current consideration. First, I think it matters to us privately. It is important for us to know if our sense of having value is something that is actually real, or if it has just been assigned to us through a kindhearted social contract. Knowing what to believe about our sense that we have value matters a lot, or at least I believe it will matter at critical times in our life.

Secondly, it matters because it influences how we come to think of others, and how we invite others to think of others. Obviously, governmental and legal protections of human dignity are human inventions; supporters of these efforts hope they will function as designed and protect the marginalized. However, they are clearly just human inventions, agreements made amongst ourselves. We will learn how well they work when powerful economic, political, social, and biological forces come sweeping through communities and cultures. Will these laws and protections be able to bear the weight of the pressure being placed on them during times of crisis? It is an open question.

However, within each one of us we need to decide how we are going to view “the other;” particularly “the different other;” the other we do not understand and of which we may be scared. How we answer the question of “invention or discovery” will determine how seriously we will take the issue of the treatment of the marginalized and the helpless when powerful forces come pressing in on us and on our circles of influence. After all, inventions can be adjusted and refit for changing needs and changing situations. Not so for that which is discovered. We may wish reality were different, we may even get ourselves and others to all agree that reality is or should be different, but those beliefs and claims, even if shared by the majority, have no power to change the truth of a discovery.

To conclude, let’s look at a story from the book of Genesis. In the 4th chapter we see the first interaction between a now fallen humanity and the God of the Bible. You know the story; there is no need to retell it. However, let’s consider just the questions that were asked between God and Cain. In verses 6 and 7, we find the first exchange. Here God asks Cain, “Why are you angry? Why is your face downcast? If you do what is right will you not be accepted?” It’s an interesting series of questions. Unpacking them might give us some insights into the human condition, and the angst and frustration that plague it. Just why are we angry? What is the cause of our discontent? Are we sure that it is others? Then a couple versus later, after the terrible deed has been done, God asks Cain a question. He says, “Where is your brother?” – a probing question of relationship and responsibility. And here Cain responds to God with a question of his own (the chutzpah of Cain is striking, isn’t it?). He says, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” What I find so peculiar is that God does not directly answer Cain. His question just hangs there in the air. The non-answer invites us all in. Are we our brother’s keeper? I believe the non-answer also invites us to consider the possibility that God, valuing people as he does, his image-bearers, has chosen to use the remaining span of 66 books to offer a resounding answer. Such is the gravity of his response. But though he does not directly answer Cain’s question, God is not done with him. He asks him one more question. In verse 10 he says, “What have you done?” What a heavy and haunting question. It is a question that brings into sharp focus our program’s theme, and it underscores the importance of determining the ultimate grounding for the claim of human value and dignity. Is it an invention or a discovery?

1The Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity. https://cbhd.org/category/issues/human-dignity

Hunter, & Nedelisky, (2018). Science and the good: The tragic quest for the foundations of morality. Yale University Press.

Pinker, S. (2008). The Stupidity of Dignity. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/64674/the-stupidity-dignity